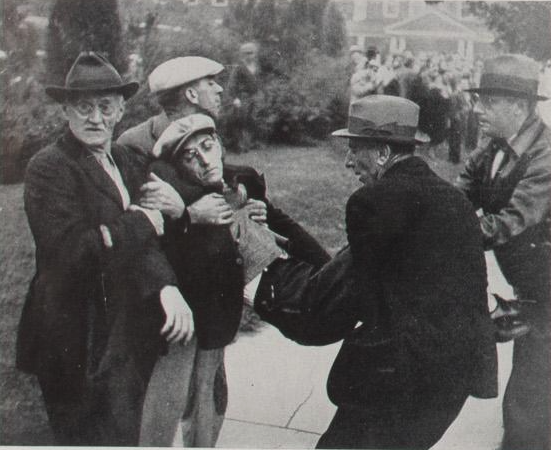

By the time dawn broke on the morning of October 1st, 1936 temperaments of the picketers were developing from bad to worse. A Reading Eagle reporter who arrived to the scene at 5:30 a.m. described what he saw as a “bitter bloody battle at the gates of the Berkshire Knitting Mills“. Thousands of picketers turned protestors gathered around the three entrance points of the mill. The main entrance at 8th and Reading Avenue was the scene of the most violent action.

Bricks were flying into employee windshields. Men and women were yelling and throwing themselves on cars trying to enter the mill. The only police on scene were local Wyomissing and West Reading officers that were easily outmanned by the mob. The crowd tipped a taxicab carrying two female workers on its side while the occupants of the vehicle shrieked for help.

To prove it was safe to come to and from work, Berkshire plant manager Hugo Hemmerich reportedly drove his vehicle through the gate past the large crowd numerous times which likely only served to antagonize them further.

A violent scene then played out which was described by the same Eagle reporter as above, “an old sedan with a young fellow at the wheel came chugging into the driveway. A blonde and brunette were on the front seat with him. The window in front towards me was open.” Allegedly a large man holding half a brick muttered, “I’ll kill him” before launching the brick through the open window, striking the young man in the head. The young man at the wheel collapsed and the now screaming women passengers had to pull the emergency brake to stop the vehicle. Members of the crowd took the unconscious man from the car and hauled him off to the Berkshire infirmary. His name was Martin Earl Schlegel.

By 7:00 a.m., nearly an hour and a half after violence began, at the behest of Wyomissing borough and West Reading officials, Pennsylvania Governor George E. Earle dispatched 26 state troopers under the command of Captain Samuel W. Gearhart to the scene to assist local officers.

In the Reading Eagle that morning, Hugo Hemmerich publicly called out William C. Bitting, head of Rosedale Knitting Mill, for closing the Rosedale plant that day; “He granted a holiday to his employees so they could take part in the demonstration, and their presence, I believe, was the cause of all the trouble. I think he is guilty of helping to incite a riot“. When Bitting was informed of Hemmerich’s statement, he replied, “He (Hemmerich) can say anything he pleases. I am not interested in anything he says“. While no other mills in the county shut down outright, all of them admitted to having workers calling out or being late to their morning shifts.

Things quieted down until shift changes occurred – at 2 p.m. and 4 p.m. respectively – when tensions flared again resulting in more broken windshields and headlights. State troopers used their riot sticks and horses to break up the crowd without hesitation. It wasn’t until the last shift ended at 10 p.m that things spiraled out of control again.

In response to being crowded a little too closely by the large number of protestors, the state troopers, clearly weary and angry from the day of unrest, unleashed tear gas bombs into the crowd. Men and women started scrambling for safety from the fumes, which lead to absolute chaos.

Sergeant Edward C. Sickel, who was in charge of police personnel on day one, alleged that the midnight bloodshed was precipitated by a barrage of stones which struck troopers. Protesters alleged that they were simply minding their own business when the troopers attacked.

With the help of the tear gas, fifty state troopers with night sticks cleared several thousand protestors off of Reading Avenue between Van Reed Road (now Park Road) and Sixth Avenue within 10 minutes. Besides police car headlights and spotlights, only one street light remained un-smashed from the day’s melee. According to the October 2nd, 1936 Reading Times, the troopers made no attempt to hide their anger and a reporter described the altercation as the “wildest, most hard fought battle ever experienced in Berks County labor history.”

As protestors retreated, troopers reformed their lines, and marched east from Eighth to Seventh avenues. Someone rushed across the street and hurled a rock at the one remaining street light source, plunging the entire area into darkness. The troopers were again ordered to charge with their nightsticks and the crowd was driven all the way back to Penn Avenue. State troopers ran up and down Penn Avenue seemingly swinging at anything and everything. This entire ordeal lasted nearly an hour and a half.

Dr. H. W. Bagenstose, who during this time was hosting eight friends on his front porch at 738 Penn Avenue in West Reading, later filed a complaint against state troopers who he claimed, “ran onto the porch without warning and without explanation and started swinging their riot clubs right and left.” Four of the physician’s guests were hit by the clubs, including a woman who had recently had been operated on for appendicitis and a man with a peg leg. The trooper hit the man’s peg leg so hard it shattered the riot club. Dr. Bagenstose said that Sergeant Edward C. Sickel was one of the three troopers who assaulted his guests.

American Federation of Hosiery Worker officials were outraged by what they described as police brutality and demanded in the form of a petition that Pennsylvania Governor George H. Earl launch an immediate investigation into Captain Samuel W. Gearhart’s handling of the events that unfolded. John Edelman, research director of the AFHW, stated “It has been many years since I saw such outrageous examples of state police terrorism.“

By October 3rd Samuel W. Gearhart was removed from commander of the troop assigned to the Berkshire strike pending an investigation of the actions he ordered on the night of October 1st. Governor George H. Earle placed Major C. M. Wilhelm, deputy superintendent of the state constabulary at the head of policing the strike area. The Governor urged both Berkshire Knitting Mills management and AFHW officials to sit down and let him mediate the situation.

Over the course of that first day, 25 people were treated for serious injuries in the hospital and 18 people were arrested. Three of those injured had fractured skulls, including state trooper Sgt. John M. Wollmer, who was hit by a flying brick during the nighttime melee and union protester Donald McCarrager, 18, who was struck with a pole by a trooper during the same altercation, as well as the aforementioned M. Earl Schlegel.

When the dust settled from day one AFHW officials claimed that the violence was the fault of Berkshire management, citing that national trouble makers were spotted in the crowd amongst the union picketers. They claimed they had seen agents for the Railway Audit and Inspection Bureau acting as guards, as well as H. C. Cummings operatives at work. Both of these groups were alleged strike-breaking agencies which the union claimed were planted to incite the violence.

The AFHW also claimed after day one that they had decimated Berkshire’s workforce and crippled production; that 75% of Berkshire employees were out or in the ranks of picketers. However Hugo Hemmerich counterclaimed 90% of his workers were in and production was not affected. The second day of picketing was scheduled to start again at 5 a.m. on October 2nd, but it would not be nearly as eventful as the first.

Reading Times Reported Statistics of the First Day of the Strike

State Troopers on Duty: 36

State Troopers on Way: 17

Deputy Sheriffs on Duty: 22

Borough Patrolmen on Duty: 15

Number of Pickets (estimated): 2,000 to 4,000

Number of Spectators, sympathizers, etc.: 4,000

A Temporary Ceasefire to Bury a Friend

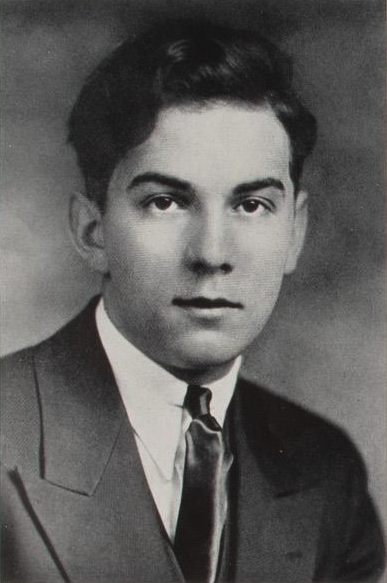

The night before the picketing was set to commence, M. Earl Schlegel was out late with his girlfriend. When he got home, his father, step-mother and two step-brothers, who were all unionized employees of Oakbrook Knitting Mills in the Eighteenth Ward, urged him not to report for work the next day. Schlegel laughed off his family member’s worry.

Martin Earl Schlegel

- 25 year old Berkshire Knitter

- 1930 Reading High Graduate

- Started working at Berkshire in July 1934

- Suffered fractured skull when protester hit him in the head with a brick while he was driving himself and two women into work the morning of October 1st 1936

- Died early morning Saturday, October 3rd

- Funeral held Wednesday, Oct 7th

When news broke that Schlegel had died as a result of his injuries, it was announced by the Berkshire Employee’s Association that, “We will make Earl Schlegel’s funeral the most impressive in the history of Reading“. Hugo Hemmerich was quoted in the October 3rd, 1936 Reading Eagle as saying, “He died trying to be loyal to his employers. We will close the plant on Wednesday when the funeral is to be held.”

Luther D. Adams, president of Branch 10 of AFHW, disbanded the picket lines for the day stating, “Young Schlegel has friends among us too.“

Thousands of employees and union picketers attended Schlegel’s funeral together as it took place on the morning of October 7th, 1936. The services were attended by Berkshire Knitting Mill owners Ferdinand Thun and Henry Janssen themselves, along with plant manager Hugo Hemmerich. Fred Werner, president of the Berkshire Employee’s Association, left the parking lot of the Berkshire with a procession of 300 vehicles carrying employees to attend.

Nearly 1200 people were packed inside Lutz Funeral home and roughly 3000 more gathered outside listening to the service through amplifiers. Throughout the viewing and service, detectives mingled outside with the crowd to gather information which might lead them to the killer.