A Storm is Brewing

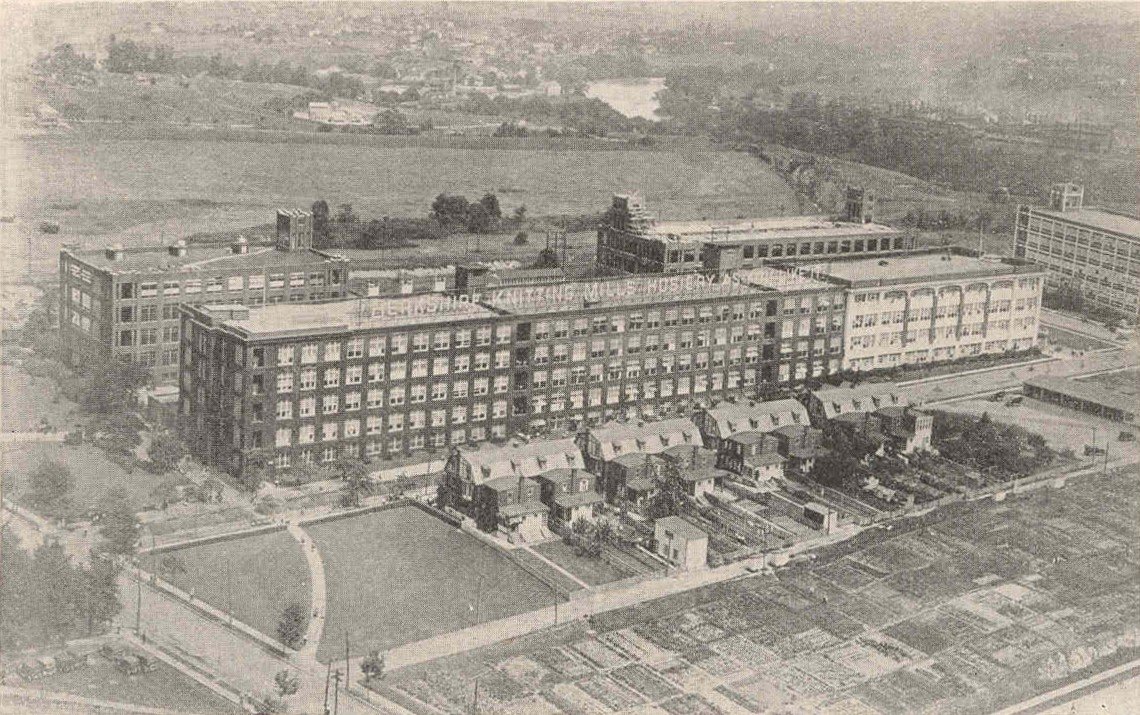

It is dawn on October 1st, 1936. It’s a crisp fall morning and a damp rain adds to the heaviness of the air. The sun begins rising at 5:52 a.m. and thousands of workers are gathering in the morning light around the Berkshire Knitting Mills plant in Wyomissing to protest what they consider violations of wage pay.

The storm had been brewing for some time. Relations were tumultuous in the 1930s between most hosiery mills and unions. The Berkshire was a special source of contention, as it was one of the only non-unionized hosiery mills in the country as well as the largest and highest producing.

A strike against a wage cut at the Berkshire had also transpired in June 1933, which at the time was labeled “one of the most dramatic incidents in the history of the American labor movement“. Ultimately, that strike was unsuccessful.

In July 1936 several hundred peaceful picketers took to Berkshire with signs alleging that management was requiring Saturday work in violation of the 40-hour, 5-day work week agreement. The mounting tension over Saturday work was enough that Research Director of the national installment of the American Federation of Hosiery Workers, John Edelman, had spent the entire summer in Berks County keeping an eye on the situation and organizing protest on behalf of the union. In many cases, picketers were brought in from other states like New Jersey to bolster numbers and prevent local workers from losing pay.

For even more context remember that the country is in the midst of the Great Depression. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, elected to his first term three years prior in 1933, has already signed some New Deal programs into place. The average citizens were still feeling the financial pinch that began almost 8 years prior with the crashing market. Partnered with the fact that the Berkshire remained one of the only hosiery mills in the industry without a union presence, this battle was one that had been fought militantly in picket lines and on paper between these organizations for years.

Earlier in September a special committee was delegated by Berks County’s Branch 10 of the American Federation of Hosiery Workers to investigate and adjust conditions which they found “so serious as to threaten the wage and hour structure of the entire full-fashioned industry of this country” at the Berkshire Knitting Mills. Because Berkshire set their own wages free of union influence, unionized plants around the country were vocal in the fact that they were not able to compete with Berkshire pricing. Berkshire Knitting Mills employed roughly 5800 men and women at this time. The committee met on the morning of September 26th, 1936 directly with general manager of the Berkshire plant, Hugo Hemmerich, to address the problems they wanted rectified. That afternoon the special committee reported to the local union leaders and a general gathering of Berkshire employees that Hemmerich had flatly refused to comply with any demands.

The committee found that the Berkshire Knitting Mills were in violation of wage and hour scales of the code working conditions followed since the abolition of the NRA*. As a result of that committee’s report, the Berkshire workers present at the meeting voted to requisition the national organization of the American Federation of Hosiery Workers (AFHW) to sanction a strike call at the Berkshire Knitting Mills.

*The NRA (National Recovery Administration) was an agency created in 1933 as a part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal to distribute available work among more workers by limiting hours and launching a public works program and increasing individuals’ purchasing power by establishing minimum wage rates. In 1935 the Supreme Court unanimously declared that the NRA law was unconstitutional, ruling that it infringed the separation of powers under the U.S. Constitution and it was abolished Jan 1st, 1936.

On the 27th, the national president of the AFHW wired his formal approval to Berks’ Branch 10, and offered any assistance needed to carry it through. Luther D. Adams, president of Branch 10 offered a statement claiming, “We have been meeting daily for past weeks with Berkshire workers checking on conditions in that plant. Today we have sufficiently complete data to state definitely that pay cuts from 20 to 50 per cent below prevailing rates have been enforced on key workers throughout the mill”.

The strike was imminent, the dread was growing, the only question was when would the picket lines begin?

National AFHW leaders wired that employees would be called out at 6 a.m. on Thursday October 1st, 1936 to picket. However, president of the Berkshire Employees’ Association, Fred Werner, announced that, “4500 employees have indicated by petition that they don’t want to strike and lose pay.” They also requested protection from Berkshire management as they tried to come to and from work. “I think the strike will be a complete flop” said Werner, “Most of us want to keep on working”. Unsurprisingly, Berkshire management promised they would do everything within their power and resources to protect the faithful workers, including police involvement.

John Edelman, research director for AFHW, admitted many workers had signed the petition but alternatively claimed that “the company pressured them into signing”. He went further to call out Fred Werner as a shill of Berkshire management. He is quoted in the September 30th, 1936 Reading Eagle saying, “‘The Employee’s Association’ is a paper organization set up by private detective agencies for no other purpose but to interfere with genuine collective bargaining.” He also alleged that during the week leading up to the strike, various departments of the Berkshire had been shut down during working hours so that ‘impartial’ persons could make speeches to the employees urging them of ample police protection if a strike took place. “The Berkshire company is peculiarly confident as to how the police will behave. How does the Berkshire know what ‘protection‘ the peace officers of the community will provide in this situation?“.

“We are adhering to the 40-hour work week, we are adhering to the two-shift set-up in all productive departments. We are adhering to the so-called ‘code wages’ set up by the old NRA and all experienced workers enjoy the same piece work rates or have equivalent or better incomes than paid by the National Association of Hosiery Manufacturers.”

Hugo Hemmerich

Berkshire plant manager in his first public statement since denying initial demands

The representatives from AFHW were adamant that the Berkshire were practicing the exact opposite of Hugo’s statement.

On September 28th Luther D. Adams of Branch 10 also called on the National Association of Hosiery Manufacturers to endorse reestablishing code rates at the Berkshire. William H. Gosch, president of the National Association of Hosiery Manufacturers and coincidentally vice president of Nolde and Horst Co. issued a statement on September 29th which said,

“The National Association of Hosiery Manufacturers will not take sides in the impending labor trouble at the Berkshire Knitting Mills. It is not the policy of the association to interfere with any problems between management and employees of any one individual mill. The association has no intention of becoming involved.”

The line was drawn, neither side was budging and the growing contention would be unleashed in a fury of violence that would claim the life of a young man and leave dozens injured when picketing commenced at 6 a.m. on October 1st, 1936.

I worked in the Personnel Office at Berkshire in the 50’s. Met so many great people!

My grandmother, a newly widowed 29-year-old mother of 3 young children, began working at the Berkshire Knitting Mills in 1935. She stayed working there for 25 years. I wonder what she thought of this strike. I don’t recall her ever mentioning it.