This is the third part in a series that will be concluded at a later date. Consider subscribing to receive an email alert when it is published. If you haven’t, read parts one & two for context.

In the wake of the violence on Thursday October 1st, 1936, the weekend kicked off surprisingly calm. Calls for peace and mediation were made by various local business leaders and the Pennsylvania Governor himself.

Two investigations were underway; one led by the newly appointed Major C.M. Wilhelm. In addition to leading the state police presence at the strike site, Wilhelm’s orders from the Governor were to look into the claims of police brutality by the union officials. The second investigation belonged to District Attorney John A. Rieser. He was on the hunt for Schlegel’s killer.

Picketing Continues

On Monday morning, October 5th, picket lines reformed in front of the big mill 6,000 bodies strong. State police upped their manpower to 125 officers. Everyone was on their best behavior. Picketers still jeered and boo’d incoming workers to the knitting mill, but didn’t dare touch any of them.

That same day union officials led a rally at the Armory. Luther D. Adams, president of Branch 10 of the American Federation of Hosiery Workers, told a crowd of 3,000 that “There’ll be no conciliation with the Berkshire mill until it meets prevailing wage and hour standards.”

By October 6th, The AFHW finally put together a 12-page formal set of demands in writing which they sent to both Governor Earle and management of the Berkshire Knitting Mill. The demands were summarized as follows:

1. Provide for conformity of hour standards set forth in the hosiery code

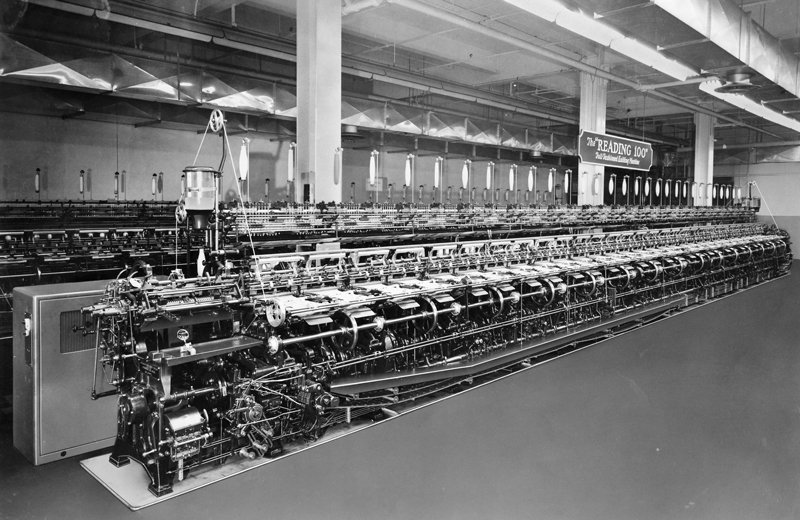

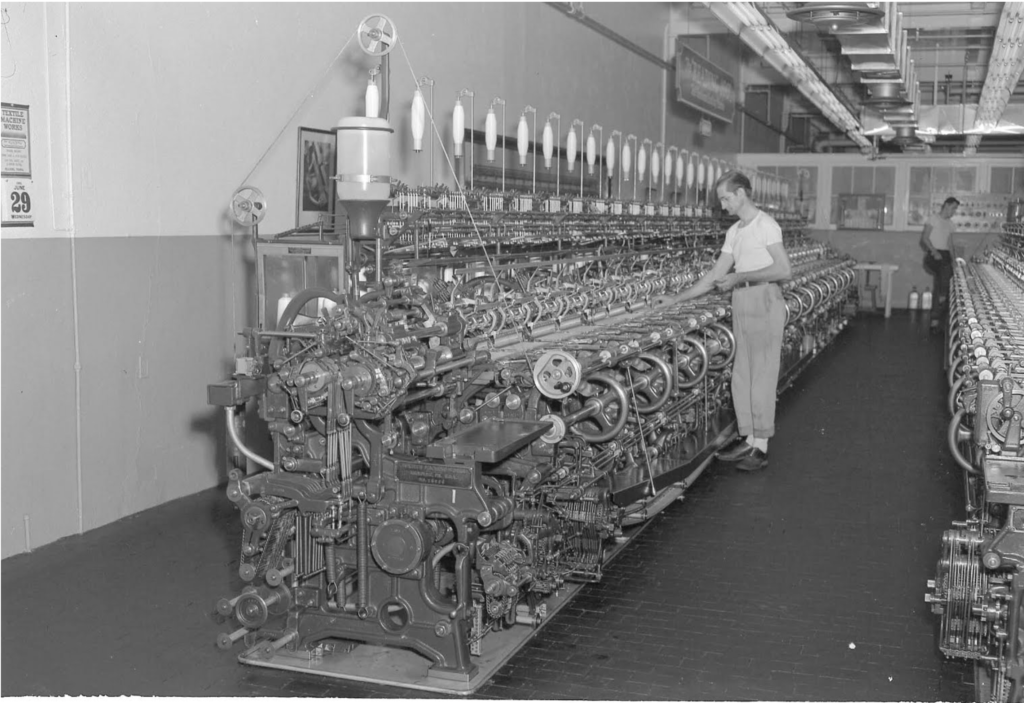

2. Establish a single machine system

3. Establish uniform piece work rates prevailing in Reading area;

4. Restore the 11.11 percent differential extra to double-shift footers and toppers;

5. Eliminate the third shift

6. Provide equal pay for equal work without sex discrimination

When Hugo Hemmerich saw the accused violations of wage and working conditions drafted by the AFHW, he stated that they were, “too ridiculous to answer“. However, he also stated he would be drafting a reply for the sake of Governor Earle.

Unsurprisingly, the Berkshire Knitting Mill formally denied all of the accusations by October 10th. They even asked Governor Earle to come to the mill to make a personal investigation into the matters. The summary of their formal response was:

1. Berkshire is conforming to the wage agreement which has been in existence since last February and which guarantees “work 50 weeks of the year at a minimum wage of $45 per week of 40 hours.“

2. It has not discriminated between sexes in payment of wages

3. It has practiced collective bargaining with the representatives of its employees and has “lived up to the spirit of the NRA while it was in effect and ever since.”

As a more specific example, the union claimed that Berkshire had implemented a contract system of wages to knitters who operated two 51-gauge machines. The industry standard was one man one machine. This created a wage below the average earned on a single machine and unemployment. The knitters could earn more under this system, but not double, which meant Berkshire needed less workers to create the same production; the margin resulting in more profit for the company. This is what the union believed to be a threat to the entire industry.

miSci- Museum of Innovation & Science

Berkshire management claimed that the income possibilities were higher than the union reported and certain men had earned up to $60 a week under the contract system. “Acceptance of this mode of operation is entirely optional and voluntary with the knitter.” Hemmerich explained.

This almost capitalistic approach to employee output was not in accordance with union standards, which is unified amount of work and a set wage for all. Knitters who chose this contract system in many cases alienated themselves from workers who did not, as the workers who did not felt the threat to their jobs and wages.

Another source of contention were the wages in the system Berkshire used to train apprentices. Michael Williams, a federal department of labor mediator said he found an “apparent advantage in labor costs to the Berkshire plant under their apprenticeship plan.” He went on to say the Berkshire plant refused a request by the federal government that it submit its wage scale for examination. Hemmerich countered that, “we did not wish the figures to go into the hands of bodies, excepting the federal government, that did not have very much to do with our business affairs in Pennsylvania.“

Plant officials, union leaders and federal and state labor mediators were invited by Governor Earle to a conference in his office the following morning in Harrisburg. Hugo Hemmerich went – along with Henry Janssen and Fred Werner – as representatives of Berkshire Knitting Mills. They met with the Governor, but flatly refused to meet with any union officials.

“We have been accused by very few people – outsiders – against the wishes of those working for us. That is why we refuse to sit down with them in the governor’s office.”

Hugo Hemmerich

October 12th 1936 Reading Eagle

Governor Earle was not very happy about the Berkshire’s refusal to discuss matters openly, and was quoted, “The situation as I see it is not alone a strike of Berkshire employees, but other mills, feeling the industry was being endangered, released their men to picket this mill. This is a very sinister and significant point to me.”

While the Governor did acknowledge it was the Berkshire management’s right to refuse mediation, he also believed they were putting themselves in the wrong by being so closed off to discussions. The Berkshire management remained adamant that it wasn’t their actual workforce striking, it was the “outside” AFHW who did not speak on behalf of their employees.

“If their conscience was clear, they could afford to sit down with the governor of the state and discuss the matter. This was a very unenlightened way to meet the situation. They certainly haven’t gained my sympathy by such arbitrary action.”

Pennsylvania Governor Earle

October 12th 1936 Reading Eagle

Upon being snubbed by management of the Berkshire, AFHW leaders completed plans to continue picketing the following morning. In a meeting with Berkshire members of the AFHW that night, leaders interpreted the refusal to arbitrate as a challenge to “fight it out to the finish“. With no headway gained and almost two weeks passed, the strike waged on at the Berkshire Knitting Mills.

Captain Gearhart Transferred

Captain Samuel W. Gearhart had been in command of State Police Troop C in West Reading for ten years by the time the strikes occurred on Oct 1st, 1936. His career had been a long and exemplary one. A few local business leaders even petitioned the governor unsuccessfully for his reinstating in command of Troop C.

Governor Earle was adamant that it was time for Gearhart to move on. By October 10th he was sent to Hershey to help at a state trooper training school. Major Lynn G. Adams, superintendent of Pennsylvania State Police, said the move had “absolutely nothing to do with the investigation of the strike disorders“.

On October 13th Wilhelm held a hearing to allow the AFHW to produce evidence of police brutality. Besides this event, Wilhelm was quoted that the investigation was practically completed on his end. Fifteen witnesses testified at that hearing about the abuse they suffered or witnessed the night of October 1st.

However, that was the last public mention of the situation in the Reading Times. By January 1937, Captain Gearhart became commander of Troop E in Harrisburg. Assumingely, Wilhelm’s investigation found Captain Gearhart innocent of police brutality, but it was never publicly reported.

Gearhart only stayed in Harrisburg for a year when he resigned to become the Police Chief for Lower Merion Township in Montgomery County. He remained in this position until his retirement from the force in 1949.

Closing in on a Killer

Fred Werner, president of the Berkshire Employee’s association, offered a reward of $1000 on behalf of the organization for anyone who would lead them to the man who hurled the brick at M. Earl Schlegel’s head. By October 6th, District Attorney Reiser announced they were closing in on the killer and had three or four suspects. He assured the public that these suspects would be able to be found and questioned quickly.

However it wasn’t until a month later on November 7th that a warrant was issued for the arrest of 26 year old Shillington native, Leslie Talley Jr. Talley turned himself in Monday morning November 9th. His bail was set at $5,000, which would equate to a little over $100k in 2022. Talley was a knitter at Oakbrook Knitting Mills, and the son of a retired state police trooper. He had worked at Berkshire roughly 7 years previous to the strike.

Talley’s preliminary hearing was set for November 16th, where the same Reading Eagle reporter who’s experience was quoted in Part Two was the key witness. The reporter, identified as Stewart Little, described the incident in even more detail than he wrote in the paper. Little testified that he was standing three or four feet behind Talley, when he “stepped out of line and threw a brick at the driver.” Little testified that Talley threw the brick with this right hand. He went on to say that Schlegel’s car kept moving slowly for about 25 more feet, and that when it stopped Talley was one of the men who helped take Schlegel out of the car.

A Grand Jury indicted Talley on December 3rd on both voluntary and involuntary manslaughter charges. His trial would begin on December 16th, and would be the most sensational of all crimes tried stemming from the Berkshire Knitting Mill strike. The court room was jammed with hosiery workers and even a few officials from AFHW.

The first two witnesses called to the stand testified that they saw Talley “throw something

into the automobile of M. Earl Schlegel”. They could not, however, verify that what he threw was a brick.

A key piece of testimony came from Dr. Leland F. Way, attending physician at the Berkshire infirmary the day of the strike. He was the first to treat M. Earl Schlegel when he was brought in by three men, one later being identified as Talley.

In the infirmary another man, who was not identified, said to Talley: “You threw that brick and you ought to be ashamed of yourself,” according to Dr. Way, and Talley replied: “Don’t talk so dumb. Why would I help to bring him in if I had done a thing like that?“.

The trial ended with Talley taking the stand in his own defense, adamant that he did not throw any bricks at that time, nor had he seen anyone else throw bricks. He did testify that as he was at 8th & Reading Avenue that morning a flying brick hit his foot. Talley claimed to have picked it up and tossed it into the parking lot. The defense asked him which hand he used to toss it. “The left hand“. Talley answered. When questioned why he used his left hand, Talley answered, “Because I am left-handed.” He did admit to helping Schlegel from the car and into the Berkshire infirmary.

The jury convened on December 19th, and deliberated for almost 11 hours. Ultimately they found Leslie Talley Jr. not guilty of both voluntary and involuntary manslaughter. No other suspects were ever charged. Justice was never served for the death of M. Earl Schlegel.

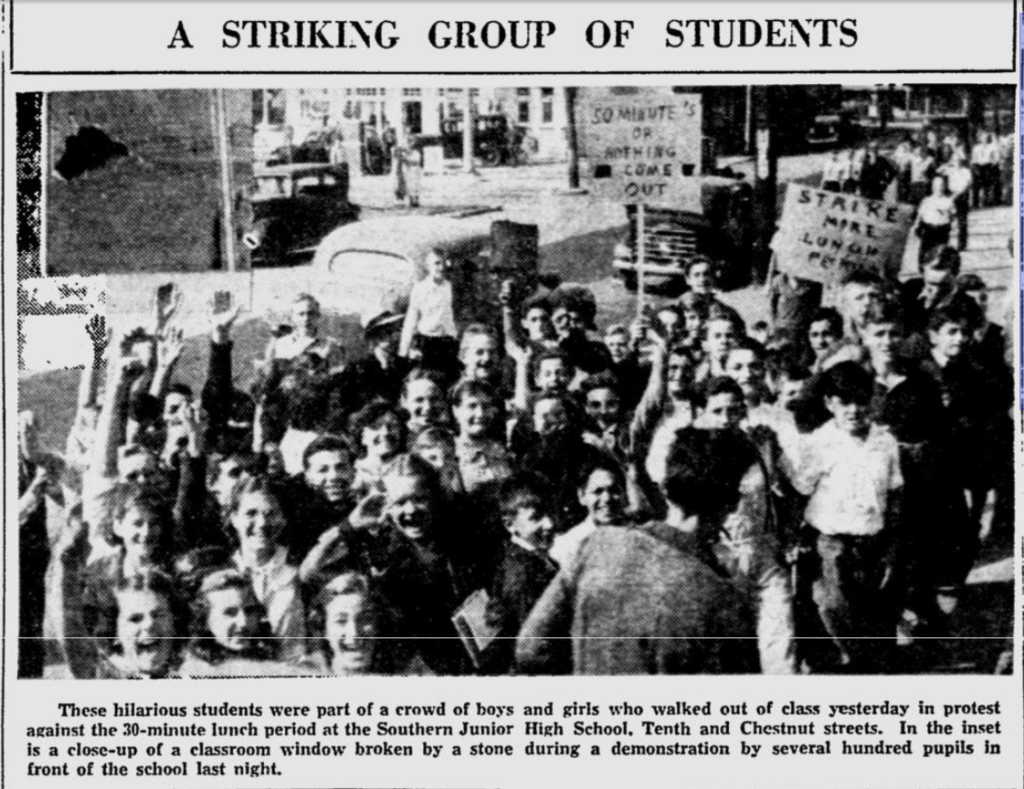

Impressionable Children

No doubt spurred by the dramatic discourse happening at Wyomissing Industries, students of Reading’s Southern Junior High School took it upon themselves to protest their own displeasure with school rules. Beginning the 1936-37 school year, lunch period had been reduced from 50 minutes to 30 minutes to discourage children from having extra time to walk home and back for lunch. School authorities claimed it was due to kids getting into trouble and loitering at places nearby, aggravating neighbors.

The students stood outside picketing and jeering for the entire Monday, October 5th, 1936 school day. When an emergency meeting was called between the school faculty and 600 parents that night, students stayed outside. Ultimately, the parents supported their children’s demands and the Principal announced that the 50 minute lunch period would be restored. Children came back to school on the 6th with a promise from their Principal that no one would be disciplined for the previous day’s walkout.