What a better time to wrap this up than Labor Day weekend? If you haven’t, read the first four parts for context.

As the weeks following the general hosiery strike played out, Berks County’s other 21 knitting mills folded one after another into signing agreements with the American Federation of Hosiery Workers.

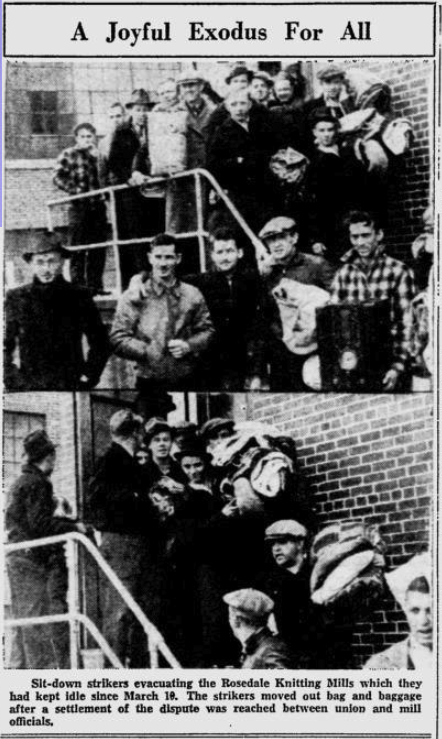

Rosedale plant was a particular source of contention – the sit-down strikers occupied the building for over two weeks while management tried to get them out. AFHW and Rosedale attorneys went at it for 5 days in a federal Philadelphia court before a conclusion was reached. In a surprising twist, twenty minutes before a judge was set to release his final conclusion on whether the sit-downers would be evicted or not, Rosedale and the AFHW reached an agreement. The strike at Rosedale was over. Strikers left the plant on Friday, March 26th, 1937 and returned as employees the following Monday morning.

On March 30th Oakbrook Knitting Mills also signed an agreement with the AFHW. By April 17th, the first blanket agreement of its kind was reached with 17 of Berks County’s hosiery mills. All but one small mill and the Berkshire were without AFHW agreements.

Anticlimactically, this is the end as it relates to the muscled unionizing of Berkshire Knitting Mills. As time passed picketers around the Berkshire diminished and things went back to normal for workers going in and out of the plant.

Conclusions & Long Term

Was it a loss for the American Federation of Hosiery Workers?

AFHW did not succeed in unionizing the country’s largest hosiery mill. They did however succeed in unionizing twenty of Berks County’s other hosiery mills and became representatives for roughly 9,000 workers. They also unionized nearly every Philadelphia hosiery mill. Berkshire was truly an anomaly not only in the hosiery industry but every other unionized industry at this time.

Did the Berkshire Knitting Mills win?

This story didn’t exactly end with the signing of the agreement concluding Berks County’s general hosiery strike. While Berkshire did succeed in fending off the union pressure it would also fight legal battles for nearly a decade at the hands of the AFHW.

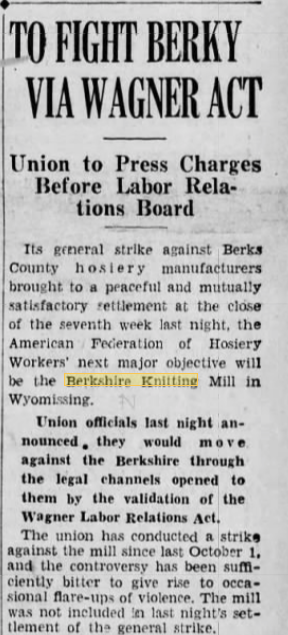

On April 17th 1937 the Reading Times Headline read like this:

Yet while the main news was most of Berks County’s mills conceding, the sub-headline indicated that AFHW was changing course as it related to matters with Berkshire Knitting Mills. While it marked the end of organized striking, it was only the beginning of a dogfight in committees and courts.

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) is an independent federal agency created in 1935 to enforce the Wagner Act. The Wagner Act was implemented to curb labor unrest. Section 7(a) of the Wagner Act protected collective bargaining rights for unions but was notoriously hard to enforce.

On November 12th, 1937 the Berkshire was summoned by the National Labor Relations Board on unfair labor practice charges. One complaint was that the Berkshire Knitting Mills management fired 303 workers for joining the AFHW while the strike was in progress and refused to rehire them. Another was that the Berkshire Employees Association led by Fred Werner was fostered by the Berkshire itself thus rendering it an interference to actual labor organization. Thirdly the Berkshire was charged with its officers making active attempts to discourage its workers from joining the AFHW through threats, speeches, and paper propaganda.

Fred Werner was the first on the stand testifying on behalf of the Berkshire Employee Association and was questioned for nearly two weeks of hearings. The NLRB probed him about the history of the formation of the organization, along with the associations ties to the Berkshire itself. Many of the 303 employees terminated by their union membership also testified. Records, letters and files were subpoenaed and reviewed. The cross examinations were often heated. Hugo Hemmerich himself took the stand. The entire investigative process took nearly nine weeks and concluded in February of 1938. The NLRB estimated it would take six weeks to reach a verdict on the complaints.

Six weeks turned into 15 months.

In May of 1939 the NLRB ordered the Berkshire Knitting Mills to:

- desist from dominating or interfering with the Berkshire Employees Association

- abrogate any contract it may have with the employees association

- desist from discouraging membership in Branch 10 of the AFHW

- desist from interfering with its employees in the exercise of their right to organize and to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing

- withdraw recognition from the Berkshire Employees Association

- Reemploy 21 former employees who are specifically named and give them back pay, minus deductions for monies received from relief jobs and other sourcces

- Reemploy 182 other employees who went out on strike in October 1936, if they apply for reemployment

- Post notices throughout the mill of the mills willingness to conform to the order

Berkshire did not roll over and accept these demands. They appealed the ruling while claiming it was ‘oppressive’. In July of 1939 attorneys for the Berkshire Knitting Mills, Berkshire Employees Association and AFHW squared off again in front of the entire NLRB in Washington D.C. for this appeal. The next verdict would be the final for the NLRB.

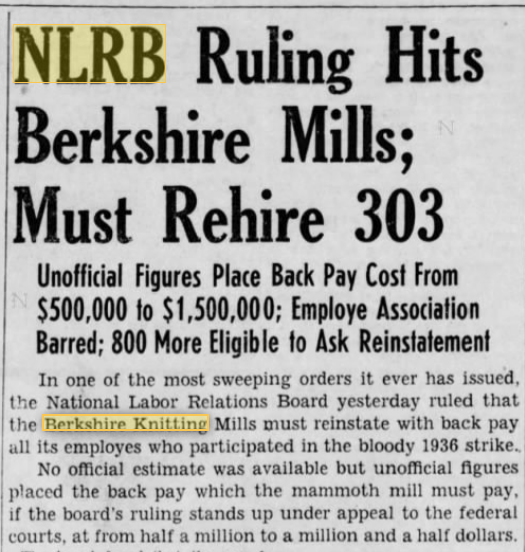

On November 4th, 1939 the final NLRB ruling was imposed on the Berkshire.

The NLRB felt that the Berkshire was in violation of all three sections of the Wagner Act in which the AFHW accused them. The board found the largest full fashioned hosiery factory in the world had “brought on the strike by its unfair labor practices“.

The NLRB’s final verdict was even more ‘oppressive’ than its initial ruling. Now the Berkshire was ordered to rehire all employees, give them backpay and dissolve the Berkshire Employees Association. Again, the Berkshire Knitting Mill management appealed to the Third U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. It stayed in the appeals court for four more years.

On December 3rd, 1943 the court finally upheld the NLRB ruling and ordered the Berkshire to disband the Berkshire Employees Association, rehire all terminated strike employees who wanted jobs and pay back wages to those who qualified. By this time the Berkshire Knitting Mills only employed 3,000 people, nearly half as many as they did when the strike occurred seven years prior.

It wasn’t until August 6th, 1946 that the back-pay checks actually went out to 662 former and present Berkshire employees. A full decade after the strikes took place. The obvious reason for the delay in justice was involvement in World War II during this time period.

By the time the back-payment checks reached the hands of those who went on strike the Berkshire was no longer the largest full fashioned hosiery mill in the world.

Nearly a quarter of those entitled to the compensation had died – most of them in the war.

Henry Janssen died in 1948 and Ferdinand Thun in 1949.

Hugo Hemmerich was promoted to Vice President and Superintendent of the mill. Poetically, he died in 1951 at work.

The AFHW underwent a few mergers later in the 20th century – now a part of the Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees (UNITE)

Berkshire Knitting Mills were sold in 1969 to Vanity Fair Mills.

This was a great series of articles concerning the Berkshire strike that many folks aren’t aware of what happened. Well done. Thanks for the research.

Very good articles.

Awesome research details on this and the other topics that you cover. Thank you

thanks for reading, Chris!

Many thanks for this wonderful five-part series about the Berkshire Knitting Mills strikes. I learned a great deal about the tense atmosphere at the time and the people involved, especially Hugo Hemmerich, who was my grandfather. He died before I was born, so it was wonderful to get more details about the man that my siblings, cousins, and I called “Opa.” My father, Karl, told me stories about the strike and the impact on our family and so many other families. In my office here in North Carolina, I have a framed original of the page from the “Reading Times” of the ad placed by the strikers entitled “Mr. Hemmerich Refuses Again!” that you reproduced in Part 4. Thank you again for helping me understand my background even better.

Thanks for reading and sharing your thoughts, Michael. Hugo’s part in the strikes fascinated me; the fact that his grandson found and enjoyed my findings on the topic made my day. I am sure your father had some incredible recollections. First hand perspective is hard to come by 90 years after something like this occurs, so hold onto those memories!

My great grandfather, Earl Frankhauser, was also involved in the strike. I think he may have been a union organizer but, I’m not certain. My grandmother (his daughter) told me that during her childhood, her parents forced her to wear the stockings that were produced at the mill. She hated them and said they were “old fashioned.” When I was going through a collection of her pictures, I found a postcard that was addressed to Earl. It was a photograph of Jawaharlal Nehur’s rose garden. Nehru was the first Prime Minister of India and participated in the 1930 Salt March along with Gandhi. This friend of my great grandfather had been to visit Nehru and wrote home about it. Although the postcard didn’t give any indication, it did make me wonder if he was there to learn about organizing non-violent protest. Perhaps it’s far-fetched but I wonder if the Berkshire strike (only 7 years later) was indirectly influenced by what was going on in India at the time.