This article was co-authored by Brian C. Engelhardt and originally appeared in the Fall 2021 edition of the Historical Review

A Man Too Modest for Who’s Who

It is ironic that the Reading Eagle’s most recent mention of the late George D. Horst was in connection with the March 30, 2014 auction of his collection of paintings that had been stored in his private museum at his Sheerlund estate located off of New Holland Road. Specifically, 64 American and French impressionist paintings from the turn of the twentieth century were sold at the auction conducted at Freeman Auctions and Appraisers in Philadelphia. Approximately 40 of which being paintings Horst had loaned to the Reading Public Museum, which he demanded be returned to him because of the Museum being “built in a swamp” in 1924. The total proceeds of the sale exceeded 4.3 million dollars; triple the amount that was anticipated.

The dramatic circumstances and events relating to the return of the art works don’t really provide an accurate depiction of the real George D. Horst.

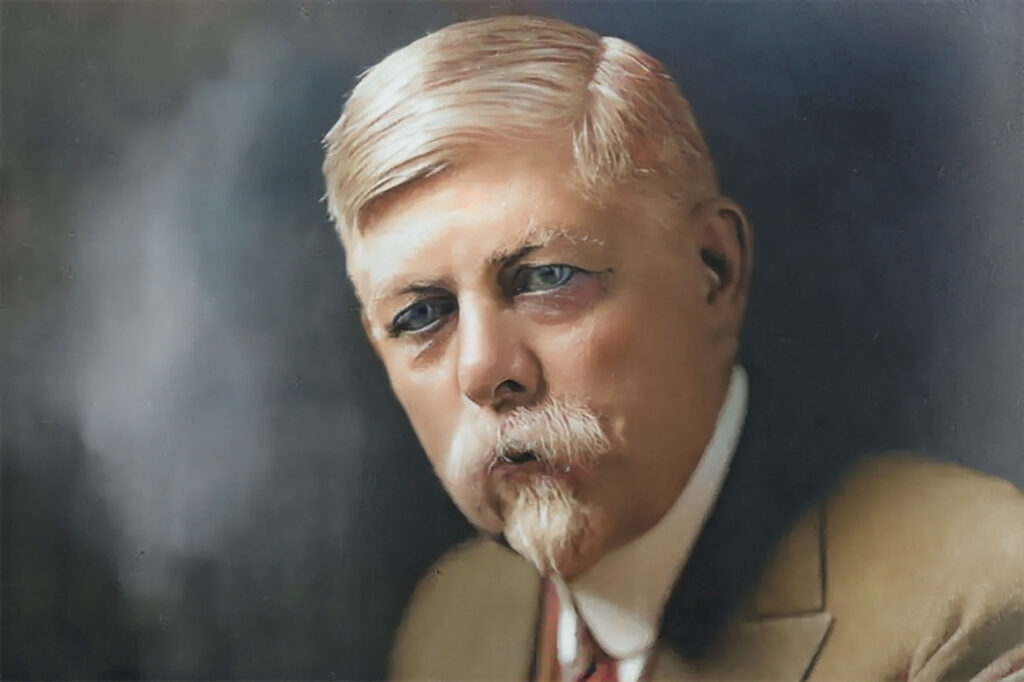

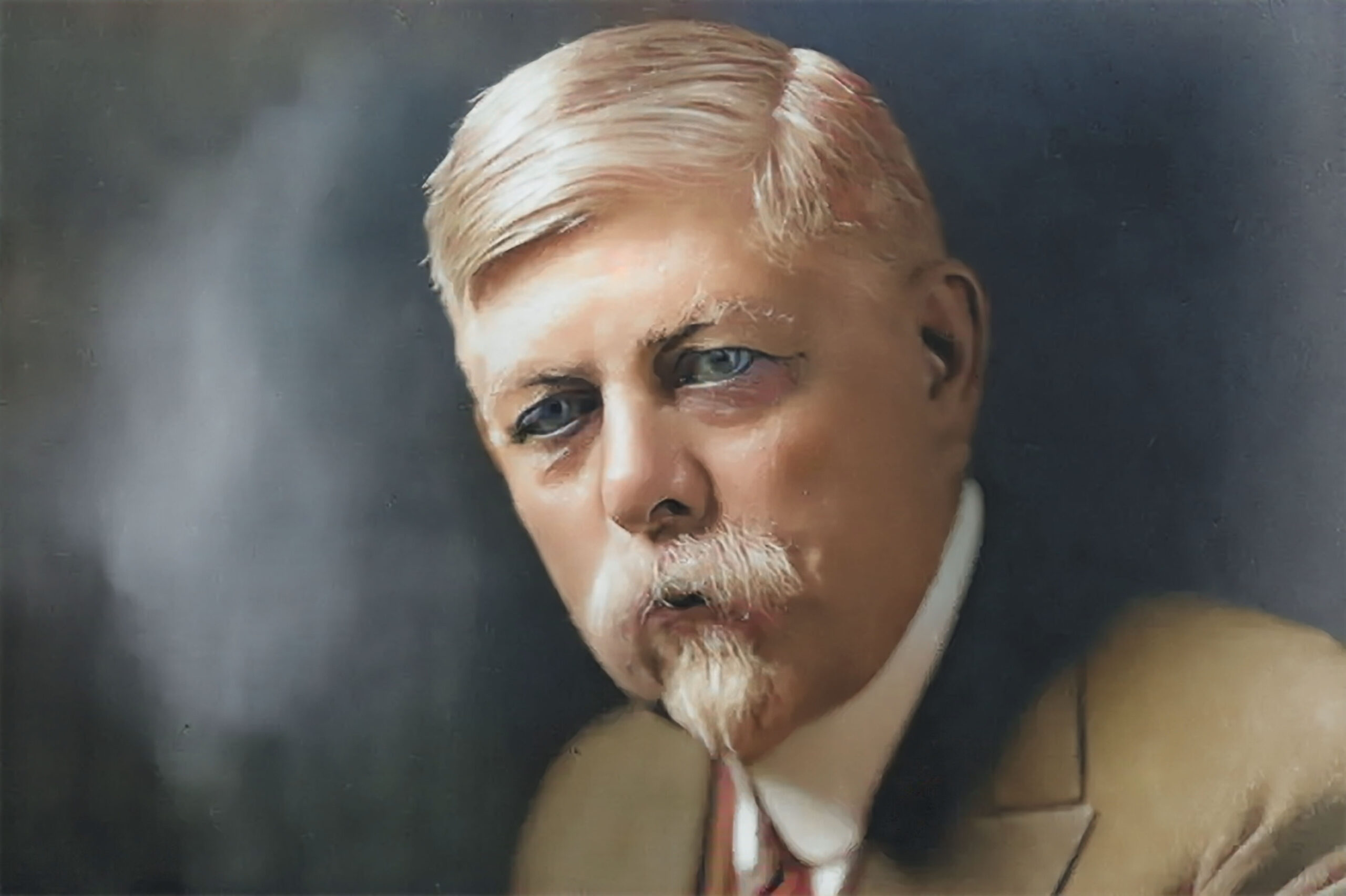

In his time a titan of the Reading business community along with being a major philanthropist, the otherwise very private and modest Horst was born in Schleswig Holstein in 1863. He emigrated to the United States in 1886 along with brothers Peter and John and a sister Louise. In 1905 he married the former Emma Goetz and the couple had one child; Caroline.

In 1890 George and John Horst partnered with another German immigrant, Jacob Nolde, and formed the Nolde & Horst partnership. Nolde and Horst for a time was the largest hosiery operation in the county. Although the massive knitting mill was virtually wiped out by a fire in 1899, by 1901 the partners were able to restore the business. When Nolde died in 1916, George Horst became president of the firm and eventually moved up to Chairman of the Board, a position he held until his death in 1934. Among Horst’s other business interests were an ownership and President of Reading Hardware Company, along with serving as a director and officer at various times in several local banks. In addition to those business interests, Horst played a major role as a real estate developer in Hampden Heights, building several of the larger homes there as well as other areas at the base of Mt. Penn. Eventually the Nolde & Horst operation was eclipsed in size by rival Wyomissing Industries, owned by two other German immigrants Ferdinand Thun and Henry Janssen.

His business interests aside, what Horst should be remembered for was the various charitable and community driven ventures, not the least of which was his involvement in the early years of the growth and development of the Reading Museum. Dr. Levi Mengel recorded in his diary that in early 1913, Horst, eager to begin an art collection for himself, had originally stated he had no interest in helping with the museum or art gallery until there would be steps taken for the operation to be “legal” to be conducted by the Reading School Board. He was concerned that donations would not be honored and returned to the donors if the operation fell on its face.

Upon Mengel’s obtaining a ruling from the Pennsylvania Department of Education confirming that it was appropriate for the School Board to run a museum, Horst immediately changed his tune and bought for the museum a painting by John R. Sharman which was the first purchase and the first painting by a non-resident in the museum collection. In the words of Mengel, “we were on the way.” Horst was a generous donor to the Museum in its early years, and loaned the various paintings that he demanded to be returned just 11 years later.

Although not a Quaker himself, Horst was an active supporter of many programs by the American Society of Friends particularly for relief work in Germany during and after World War I. Other causes he supported ranged from his being a major supporter of Reading Hospital, to the development of the 11th and Pike playground. His generosity to Albright College facilitated its early growth in the Hampden Heights area, as he contributed large tracts of land along with various financial contributions, including the amount needed to acquire the former Circus Maximus as an athletic field which is now Shirk Stadium.

Probably Horst’s most notable contribution to the Berks County community was grounded in his 1923 purchase of the bankruptcy of the defunct Gravity Railroad and its various rights of way on Mount Penn. In 1933, the year before he died, Horst gave those rights to Berks County – on which Skyline its Drive would be constructed. A small problem following Horst’s death in 1934 was a lack of documentation for the conveyance. That, however, was ultimately worked out in the courts. Suffice it to say justice triumphed and we have Skyline Drive to enjoy.

Given his wealth, Horst was a private and modest man, his obituary relating that he belonged to no civic clubs, his only memberships being in the Berkshire Country Club and the Wyomissing Club. He enjoyed chess, walking and reading in his observation tower discussed below. His grandson George Sullivan shared a letter that Horst sent to “Who’s Who” in response to a solicitation to provide information, excerpts from which show that Horst also possessed a very dry sense of humor:

January 3, 1907

Mr. Henry B. Lamb

Boston, Massachusetts

Dear Sir:

I am in receipt of your flattering request for a biographical sketch, but I am sorry to say I would not like to fill out your Data Bank. It would not look well in print on account of the monotonous repetition of the word “none” all down the line. The history of my life has been like the “short and simple annals of the poor,” and it will no doubt continue to be short and simple to the end. I am 44 years old, rather stout and inclined to be lazy, and according to my most intimate friends my “career of active work” has not commenced.

Ancestors I have none to speak of, unless I go back to old Adam, whom you know of. He got himself disliked in the upper reaches of society as then constituted, and you would hardly call him distinguished.

I never held public office; I should have served on a jury once, but my name wasn’t reached. As a slight public service I might mention that I saved this great and glorious country three times by voting the straight Republican ticket, but that I considered my simple duty.

I have no degrees, honorary or otherwise, and am not even a Mason or an Odd Fellow. Works of Art, Inventions, Scientific Investigation and Discovery are not exactly my strong points, although I did invent an improved game of poker in which you can open on any pair from deuces up and don’t have to have jacks. This has gotten to be very popular hereabouts, especially on Saturday nights.

Nobody has ever written very much about me. Once a Philadelphia newspaper got me confused with a notorious horse thief, but I showed them that it wasn’t me, and the laugh was on them. It was the Philadelphia Times, and they went out of business shortly after this disappointment. I have lost the clippings, however, so you will have to take my word for it.

Yours very truly,

George D. Horst

Horst’s prominence in the community was demonstrated in 1931 by the selection of a name for the then-budding community sandwiched between Reading’s 18th ward and the Cumru Township line. Along Lancaster Avenue bordering the 18th ward was the Kendall farm, known as Kendall Park, with the Horst properties located on the other side next to New Holland Road. The two names were combined to create the borough of Kenhorst. Horst apparently hated the idea of having a municipality bearing his name. In contrast, the name of Horst’s partner Jacob Nolde will always be remembered by the fact that Nolde Forest State Park is located on New Holland Road right across from Horst’s former Sheerland estate.

The Sheerlund Estate

Horst’s Sheerland estate was as impressive as the career and business achievements that enabled him to afford it. The tract originally served as a summer home for the Horst family, as their main dwelling was in Reading. The property was adjacent to a magnificent example of Georgian Renaissance architecture, which was the home of George’s brother John Horst, which has since been restored and is the residence of the Peter Carlino family, discussed further below.

Horst bought the first parcel of what would become Sheerlund in 1901; with his Victorian, half-timbered mansion being completed around 1910. It was built into the north facing side of a shaded hill which was likely a calculated attempt to combat the lack of air conditioning in the summer. In the 1920s wife Emma Horst told her husband that she was tired of moving everything to Sheerlund in the spring and back into town in the fall, “We either stay in town or come out here to Sheerlund”. So began the family’s permanent residence at Sheerlund.

Directly to the west of the mansion was a beautiful garden, which while currently bare of vegetation still exists. About 100 feet to the east was Horst’s museum erected to display the various pieces of art he collected- particularly those which he had removed from the Reading Public Museum in 1924. The architecture of the museum was built to be very similar to the mansion: half-timbered and Victorian in style but quite a bit larger, with a number of Germanic touches.

Another feature of Sheerlund was an observation tower at the peak of the hilltop overlooking the valley. It was built in 1910 by George as his own personal spot to read and relax. There was a walking path from the previously mentioned garden that led directly up to the tower, as well as other hiking trails on the hill. Family picnics and parties were also held at the tower as there is a most spectacular view from the top. If there appears to be a striking resemblance between this tower and a tower at the Encompass Health rehab hospital site on Route 10, its because owner Isaac Eberly, of the Oakbrook Hosiery Mill, purchased the tract of land from Horst in which he would build his “Stone Manor” mansion; he decided that he wanted to have an observation tower just like his neighbor.

Two barns constructed on the property housed George’s prized dairy cows. His fully functional dairy farm was operated on the estate for a number of years. However, most alive today associate Sheerlund with Christmas trees. The Christmas tree farm business began shortly after the second World War by George Horst’s son-in-law, Robert J. Sullivan. That business successfully operated for eight decades until George’s grandchildren discontinued the retail operation in 2012 then sold the property.

A state-of-the-art swimming pool was constructed southwest of the mansion in 1922 as a gift to George and Emma’s only child, Caroline, for her 16th birthday. This pool was the first of its kind for Berks, and attracted those of local and international importance. Caroline entertained the brother and sister dance team of Fred and Adele Astaire at her pool when they would be in the area to perform at the very popular Galen Hall Resort. Up until the time of her death, Emma Horst maintained correspondence with the dancing duo’s mother and chaperone Johanna “Ann” Austerlitz.

Throughout the decades other homes, carriage houses, and out-buildings were constructed on the property. Many housed family members and hired workers that maintained the roughly 500 acres that made up the Sheerlund estate. The last parcel was purchased by George shortly before his death in 1933, and was ironically right in the middle of the valley, surrounded by properties he already owned.

Due to Sheerlund’s location in a valley and extensive number of buildings, significant drainage and landscape planning needed to be done early on. This project was contracted and completed by Frederick Law Olmstead’s firm; famed landscape architect of New York City’s Central Park and widely regarded as the founder of American landscape architecture. Like his neighbor and business partner Jacob Nolde, Horst planted a variety of fir trees on his estate encompassing the hillside.

Following George’s death, Emma Horst continued to live in the original mansion until her death in 1956. It then sat vacant until the early 1980s when it was demolished due to its derelict condition. In 2014 following the closing of the Christmas Tree farm, Horst’s descendants sold most of the property that was once a part of the complete Sheerlund. It was purchased by local businessman Peter Carlino, locally renowned for his redevelopment projects in downtown Reading as well as being the first CEO of the highly successful Penn National Gaming. At that time, most of the other significant structures on the property, including the museum, tower, pool and numerous outbuildings that served as homes for caretakers of the estate still existed.

Since purchasing the Sheerland tract, Carlino has made caring for and maintaining the Sheerlund estate his personal project. Rather than see the historic buildings razed and valley hillside redeveloped, he chose to renovate the remaining buildings and preserve the historical nature of the estate George Horst built over a century ago. The museum, tower and various other outbuildings on the property which were once in disrepair have all been restored and modernized as to plumbing and utilities.

The barn that once housed Horst’s dairy cows has been renovated into a state-of-the-art facility; currently home to Carlino’s prized thoroughbred racehorses. Like Horst, he has a team of workers to maintain the grounds or train and care for his horses. His future plans include adding longhorn steer to the collection of animals roaming the vast green fields of Sheerlund. Although none have yet been introduced to the operation of the farm there, however Carlino reports that they are close to completing a major ring or arena to work them, plus now have what he recently described as “ten beautiful cow horses”.

Currently, Carlino has no plans to utilize Sheerlund in any sort of commercial or public way (it is private property with an abundant number security cameras). His renovations, hobbies and love of the history behind his estate are merely a financial endeavor which he has undertaken solely for his own personal satisfaction. Similarly to George Horst, he is a fairly private man who puts extensive time and effort into his business, family and Sheerlund, as well as various hobbies. The individual parallels between the man who created Sheerlund and the one who restored it are palpable.

(Note: For more information on Sheerlund, the Nolde estate, and their original owners, see “A History of the Governor Mifflin School District, Volume 2,” by the Governor Mifflin Historical Society, 1989, a copy of which is in the Janssen Library at the Berks History Center.)

The authors extend their sincere thanks and gratitude to Peter Carlino and to George Sullivan, grandson of George Horst, for the time they provided in interviews and in Mr. Carlino’s case, giving a tour of the renovated grounds.

Wonderful work. Extremely interesting.

I agree with Mr Horst- I think it would have been great at city park. Lovely article

Thank you. I have wondered about both of these observation towers for a couple of years, now. An interesting history about these.