At 1120 Centre Avenue sits the Stirling Mansion, crown jewel of the Sternbergh Estate; one of Reading’s most extravagant industrial-era homes. It was built for iron and steel industrialist James Hervey Sternbergh, who constructed the estate on land that was in 1890 rural Centre Park. Built in Châteauesque-style based on French revivalist architecture; the home is a prime example of the wealth that American industrial cities like Reading accumulated by the turn of the 20th century.

Chateauesque style traditionally features heavily ornamented towers, spires, and steeply-pitched roofs reminiscent of sixteenth century châteaux. It was one of the less popular architectural styles of the Victorian Era, and the Stirling stands visually unique amongst the other mansions of that era that sit along the Centre Avenue corridor.

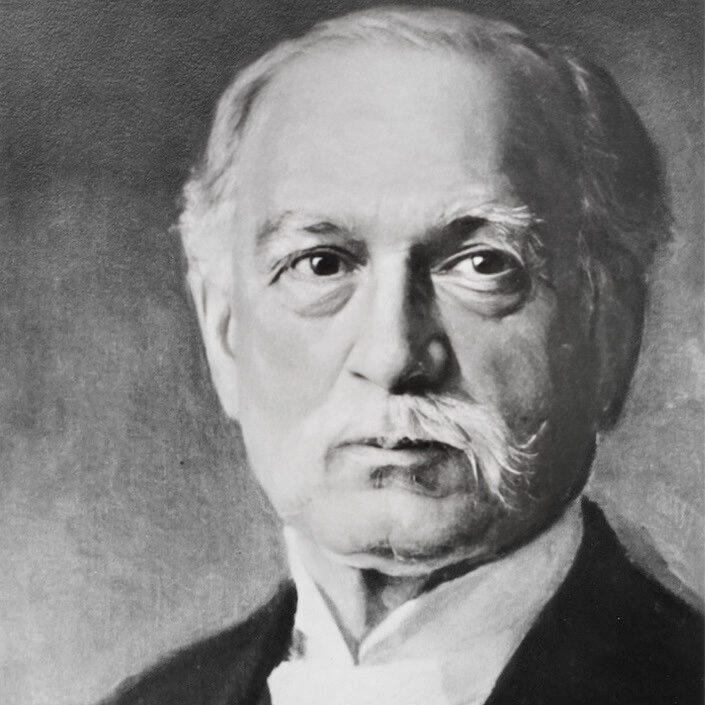

James Hervey Sternbergh

James Hervey Sternbergh was born in New York in 1834 into a farming family. He spent many of his younger years as a railroad passenger agent and decided to move to Reading in 1865. He quickly became involved in the manufacturing of bolts, nuts and rivets. It was said that when Sternbergh first came to Reading he was merely passing through to Pittsburgh on the railroad, but the breathtaking view from Mount Penn made him choose this place to build his life.

In 1867 Sternbergh invented and patented a machine for making hot-pressed nuts which quickly became in demand due to its efficiency. He also invented a variety of other machines to make the process of manufacturing steel and iron products more cost-effective and quickly began to grow his fortune. He founded the Reading Nut and Bolt Co, later renamed J.H. Sternbergh and Sons, which was bounded by 3rd and 4th Streets, Buttonwood Street and the railroad tracks.

He was married first to Massachusetts native Harriet May in 1862 with whom he had five children, and unfortunately survived all but the youngest two. Harriet passed away in 1886 of of a pulmonary affliction of which she suffered for many years. She spent extensive time on trips to the Alps in Europe and later Colorado to find relief from her symptoms. She died in their home at 530 North 4th Street (now 620 Centre Avenue), which is where the Sternbergh family resided previous to the construction of the Stirling.

In 1888 he married Mary Candace Dodds and fathered six more children. Sternbergh purchased the four-acre property at 1120 Centre Avenue from Julius Hertwig in 1890, and the deed described it having buildings and being known as “Andalusia Hall“. The property is located directly across from Charles Evans Cemetery, which was a very rural area at that time. The May 23rd, 1859 Reading Times describes Andalusia Hall as “the popular [summer] resort opposite the cemetery” which was owned and operated by James Madeira. Judging by the Times archives, many popular gatherings were hosted there between the 1850s-1880s.

Like most resorts of the era, popularity waned by the end of the 19th century, thus giving Sternbergh the opportunity to purchase it. He demolished the Andalusia Hall structures and began construction on his Stirling Mansion in 1891. Inspiration for the name came from the Stirling Castle in Scotland. It was designed by Theophilus Parsons Chandler, a prominent architect in and around Philadelphia. It was completed in 1892.

The Stirling Mansion boasts 24 rooms; eleven bedrooms, ten fireplaces, and nine baths encompassing over 15,000 square feet.

In 1899 Sternbergh founded the American Iron and Steel Manufacturing Company, which he ran for seven years before retiring in 1907. Eventually it was bought out by Bethlehem Steel, who operated it as their Reading Plant, which closed permanently in 1926. Sternbergh was also instrumental in founding Reading’s Y.M.C.A. and had a hand in various other local enterprises, including interests in an automobile manufacturing business called Acme Manufacturing Company. He was also a director of the Second National Bank of Reading, and was also President of the East Pennsylvania Railroad.

The Sternbergh family also owned a farm near Burlington, Vermont where they typically spent several months in the summer.

Sternbergh died of bladder cancer in March of 1913 inside the mansion. His estate was reported to be $2,661,088, including the mansion valued at at $75,000. That would equate to over $85 million in 2025. Notably his widow Mary and her children inherited everything as directed in his will. His two surviving children from first wife Harriet received but $5000 split between them which was from an insurance policy on their mother’s life. This was later reversed by the Pennsylvania Surpreme Court. Sternbergh also left $10,000 to the Reading Hospital, as he was serving as its President at the time of his death.

Mary Dodds Sternberg lived in the home until her own death there in 1938. Youngest daughter Gertrude then assumed ownership of the Stirling property, as she was the only child who remained unmarried and still living at the Stirling at the time of her mother’s death. The mother-daughter duo loved to host high-society gatherings at their mansion, including card parties, luncheons, dances, and musical acts.

Gertrude Sternbergh

Gertrude was born in the mansion in 1899, the last of the Sternbergh children. She was a talented pianist, evident by the five pianos on the main level of the mansion. She learned first from her mother as a child, but by the age of 13 was taking formal lessons in Philadelphia. In the 1920s she began studying under renown Russian pianist Josef Lhevinne and by the end of the decade graduated from Juilliard School of Music.

She made her debut performance with the Reading Symphony Orchestra at the Rajah Theatre in December of 1924. Music was her life passion, as she was an active benefactor of the Reading Symphony Orchestra and instrumental in the Reading Musical Foundation. She was also involved in the Junior League of Reading.

A local and international socialite and debutante, Gertrude described what a wonderful time it was to be alive in the roaring 20s, “Reading was really a party town. It was very gay and very elegant. We used our best china, our nice silver. We all stood out. And we all dressed nicely. It was an awful lot of fun, lots of competition, who wore what, who said what, who went with whom, all that kind of thing. It was a very exiting time to be young“.

Later, Gertrude taught her own piano pupils. She discovered and hosted the talents of musicians like Jerome Hines, Andre Watts, and Franco Gulli. She continued the tradition of utilizing the mansion as a place to host causes and people she cared deeply about. The halls of the Stirling were frequently visited by artists known all over the world.

Gertrude married later in life to Hans J. Vetlesen and never had any children, which she stated was one of her biggest regrets. Despite her great wealth, her self-awareness made her seem normal, “It’s a twist of fate that I was born with a little income and was free not to work…it didn’t make me a better person. It’s all an accidental gift and should be considered so.”

The Stirling Mansion was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

Like her parents, Gertrude also died in the mansion on January 28th, 1996, bringing her life there full circle. A March 14th, 1982 Reading Eagle article about her and the mansion quoted her, “I absolutely adore this house. There’s a certain affinity between me and this house. I just couldn’t imagine being separated from its walls, its era, its dignity. I just couldn’t imagine saying goodbye to it.” She never had to.

The Gables at Stirling Bed and Breakfast

In 1997 the property was sold to Kaj Skov who began operating a bed and breakfast in the mansion. In 1998 the Carriage House which sits behind the mansion was converted into more living space for guests to stay. Skov also turned the property into an event venue, which included hosting countless weddings during his ownership. In 2020 it was purchased by Cesar Gonzales who has continued operations in that capacity. The property is currently on the market again and is pending sale. Hopefully the buyer is one that can preserve not only the intricate details and magnificence of the Stirling Mansion, but also embodies Gertrude’s lively spirit and love for its walls.

“I am so crazy about living, I can’t tell you how excited I am about every sunset, every leaf on the tree. Every summer noise is just heavenly. I don’t want my ears to be stopped up, or not be able to see. And that’s what happens to all of us, even you, dear. It’s just that we got on the train at different times, is all. It’s the same train, same speed, forever.” – Gertrude Sternbergh

Beautiful article!

The harpist in the picture looks very much like Edna Phillips, longtime harpist for the Philadelphia Orchestra who was a native of Reading!

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edna_Phillips

No way to be sure, but the dates match and Miss Sternbergh loved to promote women in music in her hometown. I’d say it’s “very likely” her.

I recall attending Gertrude Sternbergh’s performance of Rachmaninoff’s “Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini” with the Reading Symphony Orchestra, Louis Vyner conducting, circa 1970. I appreciate this article about her and her family history, and also that beautiful house (with five pianos!).