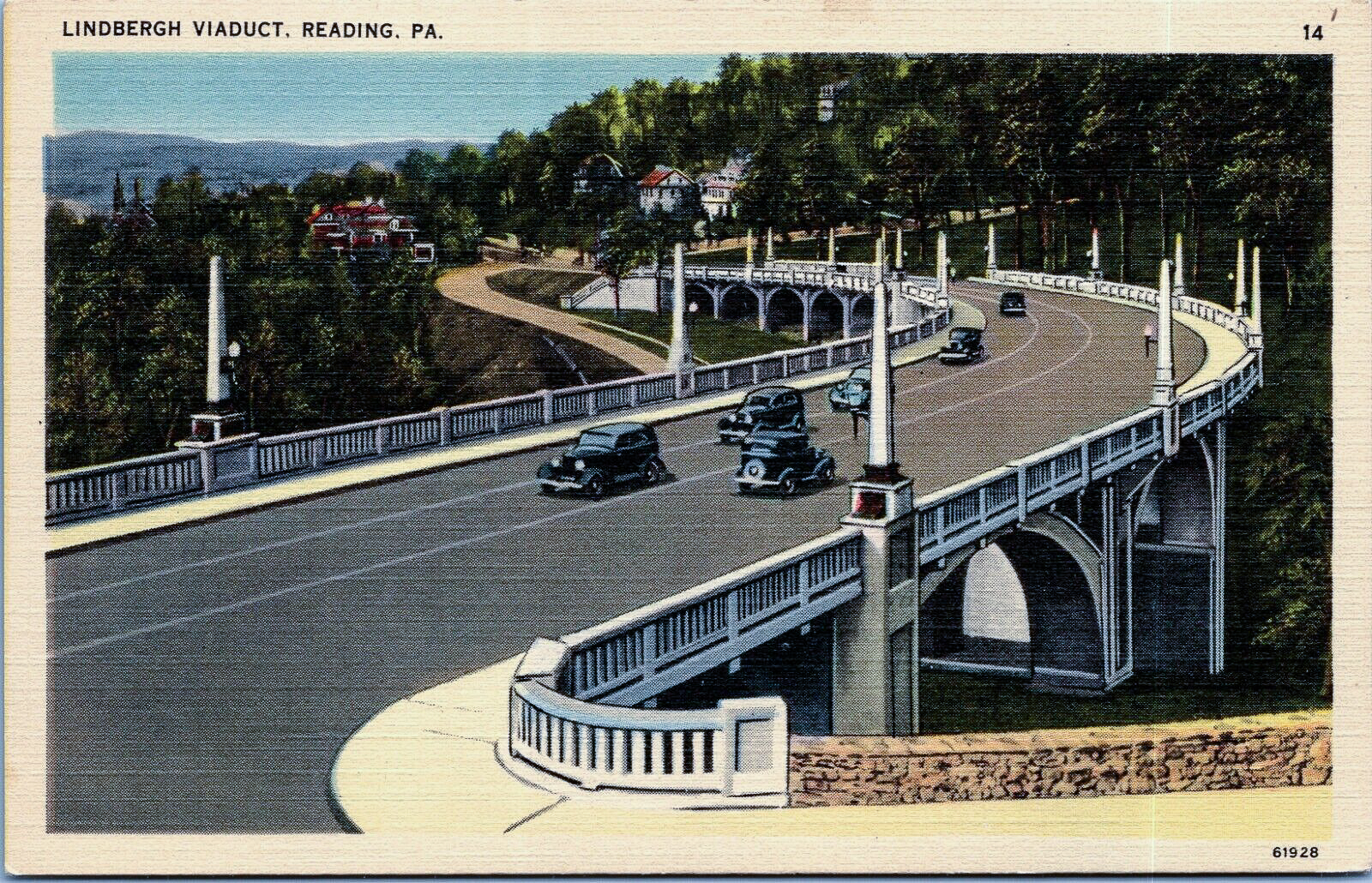

In the early 1920s there was no easy way to get to Reading proper from the east; the direction of metropolitan Philadelphia. Traffic generally came through rural Exeter Township, into Mount Penn, and down the two lane Perkiomen Avenue. By 1925 with the increasing availability of the automobile it was clear that the small residential road was becoming dangerously overrun with traffic. Newly elected Mayor William E. Sharman proposed a new road plan to alleviate it.

By the summer of 1926 the project gained momentum. Financial collaboration was promised from Mount Penn borough as well as cooperation from Aulenbach’s Cemetery. A viaduct was to be built connecting Mineral Springs Road and Perkiomen Avenue. In July of 1926 the Reading Times reported that city council secured a $850k loan to make the idea a reality. However, the now-iconic bridge was fraught with unfortunate events from its very inception.

Also in the summer of 1926 the 14th and 15th wards were struggling with water issues. These areas were amongst the newest developed parts of the city. During this particularly dry summer, the Penn Street reservoir failed frequently, cutting them off from a water supply.

Citizens of the 14th and 15th wards demanded city council reallocate the $850k loan for the viaduct to sewer improvements in their districts. It was reported in the August 20th, 1926 Reading Times that A. W. Frobey, board member of an organized group of 14th and 15th ward citizens to fight for sewer changes stated, “Reading would become the laughing stock of the state if a bridge were built over a piece of ground where there was no water”. Despite this hiccup of what Mayor Sharman deemed to be “political poppycock“, he and city council did not budge and the viaduct plan marched on.

County engineer Charles F. Sanders was hired by the city to design the viaduct at the end of 1926. Sanders began his county engineer position in 1903. During those 23 years he was responsible for designing and overseeing the construction of more than 75 bridges in Berks County. Some of the most recognizable include the Penn Street Bridge, Schuykill Avenue Bridge, Bingamen Street Bridge and the Birdsboro Viaduct.

Ground was broken on the project in the spring of 1927. In June, Wyomissing resident E. D. Kains proposed in the Reading Times to name the bridge after aviator Charles Lindbergh, who weeks earlier made the pioneering transatlantic flight from New York to Paris.

Sanders was granted leave of absence in July 1927 following a mental health crisis he endured as result of overwork in designing the Lindbergh Viaduct. With over two decades of experience building Berks County’s most recognizable bridges, what about the creation of the Lindberg Viaduct sent him over the edge?

Many issues developed during the initial construction process. When digging to pour the concrete bases for the viaduct’s pillars, sand pockets were hit which required redesigning parts of the bridge. In fact, the eastern approach had to be completely reconfigured to accommodate this problem. The projected cost was initially estimated to be around $338,000. As a result of problems encountered there was a $40,000 addition in expenses by September 1927.

It has been a longstanding rumor that the Lindbergh Viaduct was the first curved bridge of its kind in the country. Absolutely no where in the course of this research did I find that to be the case, as it most definitely would have been mentioned in any one of the articles linked about the construction process. The curve was only mentioned as it resulted from necessity from the angle of approaches and avoiding the sandy soil in which the supportive columns could not be placed.

Sander’s mental state was so bad he left for the west coast to seek relief. The Sept 16th, 1927 Reading Times reported he was recovering his health on a tour of the west, visiting Mexico, Southern California and Los Angeles.

On September 28th, 1927 the first death occurred as a result of the bridge. Carpenter Alvin Adams fell 50 feet after having a premonition about his own untimely demise only days earlier. It was reported in the September 29th Reading Times that Adams had told his father that he didn’t think he would live to be his age.

On December 7th, 1927 the very first motor vehicle made its way onto a bridge even though it was not yet open to traffic. A Union Fire Company vehicle was called to the viaduct to put out a fire which had engulfed a hoist.

Sanders didn’t return to his duties as county engineer until new year 1928. On May 2nd, 1928, he official resigned the position, weeks before bridge was set to open to public. He was quoted in the May 1st, 1928 Reading Eagle, “I feel that after a quarter of century as a county engineer I ought to have more time to devote to my personal affairs”. After a 4 year hiatus Sanders would be reappointed county engineer on January 1st, 1932 only to die days later of pneumonia.

The Lindbergh Viaduct opened to public traffic on May 28th, 1928 and the final cost with all changes and improvements was $764,000.

On November 2nd, 1927 Mayor Sharman took out an entire page in the Reading Times using the viaduct as an advertisement for his re-election. He was defeated. On September 13th, 1928 it was reported in the Times that the city received a bill for $47,000 for land that the viaduct was built on. “They made the bridge crooked to hit this piece of ground and then they didn’t pay for it,” declared city councilman Maurer, “This viaduct is a failure, nobody wants it and those that do use it run a risk of accident every time they go over. It is a miserable thing and now we must find the money to pay for it. I wonder if there is no end to this thing.”

Sharman’s successor was socialist Mayor Henry J. Stump. Sharman’s defeat was attributed to socialist propaganda at the time which indicated that Sharman received kickbacks for changing the approach of the viaduct to a piece of ground which belonged to his brother. He allegedly then received some of the eminent domain proceeds. This claim was never substantiated.

A common joke of the era was, “Why isn’t the Lindbergh Viaduct straight? Because it’s crooked.”

The first reported accident on the bridge occurred on October 25th, 1928 when two people were injured due to slippery conditions. Skidding would be a reoccurring problem on the bridge and led to many accidents. However even after multiple attempts into repaving the span to remedy the problem, it kept happening.

On April 30th, 1936 a fatal crash occurred on the Lindbergh Viaduct which killed one and injured 6 more.

The very first suicide occurred on January 31st, 1938, when a city employee who had recently quit his job took his own life by plunging off the bridge onto the tennis courts below.

The West Shore bypass was completed in the early 1960s, negating the need for the Lindbergh Viaduct to carry traffic from the east into the city. However, the bridge has remained the location of many accidents and suicides to date.

In March 2021 a man was tragically killed in a freak accident when a tree fell on his car which was traveling on the viaduct. Most recently in January of 2023 a body was found under the viaduct. Perhaps another tally in the nearly century old list of those whose last moments are indelibly connected to the structure.

Love to see a piece on Abe Minker, Stan Kubacki, and the cleanup campaign of Mayor

Shirk. The red light district around Franklin Street Station, the bribes, the Feds. A guy came to our house to take numbers bets from my grandmother. ( now the state makes it easy ). As a kid, I thought it was all normal. She always bet her grandsons’ birthdays.

The 20th century corruption is a fascinating topic. Definitely something for me to look into. Thanks!

Loved the article, and the awesome postcards. Used to walk the viaduct every day to get to Central Catholic in the 70’s. Politicians have been nasty forever. I don’t see going West as a mental health treatment today!