Have you heard of the name Stoneman Willie? Have you lurked at the front entrance of Auman’s Funeral Home, working up the courage to ring the bell and ask for a peek? Are you a part of the exclusive club who have actually seen him?

If you are or ever were local to Berks County, Pennsylvania you have likely heard the legends, but what is his truth? Why is he above ground 128 years after his death?

The inception of this story dates to the fall of 1895, when a man died without much affair in a cell at Berks County Prison. Thousands of curious children and adults have made their way through the portal of Theodore C. Auman’s Funeral Home over the course of the 20th century to get a glimpse of his hardened corpse. A morbid, yet fascinating tale – the truth about Stoneman Willie is not as elusive as it once was.

So what is the real story behind Berks County’s most famous mummy? Advances in technology have allowed for thousands of historical records to be made available and searchable by keywords. Sleuthing this digital paper trail has led me through twists, turns and truths which provide context to his story. Referencing original articles in the Reading Eagle, Reading Times, Philadelphia Inquirer and beyond; this account is going to take you chronologically through the series of events which led to Stone Willie’s unassuming 128 year slumber on the 200 block of Penn Street.

Stoneman Willie’s Story

The first week in October of 1895 brought the State Firemen’s Convention to Reading, Pennsylvania. The event was highly anticipated and attracted members of firefighting organizations from all over the region. On October 2nd, a parade for the occasion was scheduled to take place on Penn Street. Events of this magnitude also attracted those who would take advantage of the influx of traffic to attempt petty crime. The day before the parade a man was arrested by Philadelphia detectives. They charged him with drunkenness and suspicion and sent him to jail for the remainder of the week in an attempt to keep him away from the crowds.

That man was released on Saturday, October 5th and made his way into West Reading. In the early morning hours of Monday, October 7th, Lizzie Dautrich, a servant sleeping in her bed at Morris Brown’s boarding house awoke to the man rummaging through her belongings. As she stirred, the man dove under her bed, and she caught a glimpse of his feet disappearing underneath. Somehow keeping her wits about her, she calmly got up and left the room, locking the door behind her. She alerted others and authorities arrested the man yet again.

The Monday, October 7th, 1895 Reading Eagle reported the man was a Philadelphian, and was burglarizing all of the rooms in the boarding house while the occupants slept. It also revealed his identity as “James Penn”, that he was well-known in Philadelphia police circles and had served time there for breaking into homes.

That same article also reported that as soon as Penn was locked up in his prison cell, he attempted to kill himself by tying his handkerchief into a noose and looping it onto the bars of his cell’s door. It failed to hold his weight and ripped. Contrary to the commonly told version of Stone Willie’s story, his death was not a suicide.

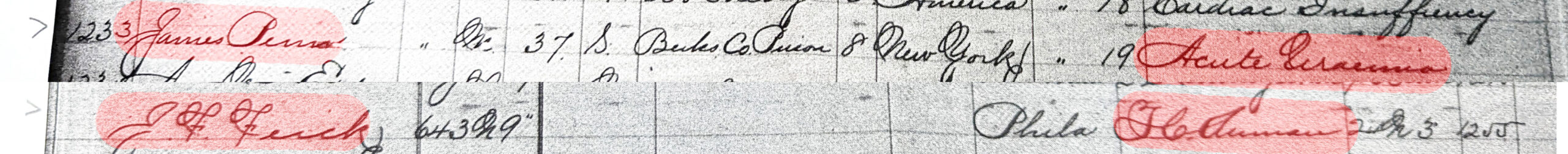

In fact, Penn wouldn’t die for another seven weeks. He spent that time suffering from what was believed at the time to be the effects of alcohol withdrawal. On November 19th, 1895, he succumbed to what prison doctor J.F. Feick believed to be acute uremia (kidney failure) as he noted on the prison’s death record. The November 20th, 1895 Reading Eagle reported that when Penn was told by Dr. Feick that his death was approaching, he revealed that James Penn was not his true name but refused to identify himself. He claimed he had a brother and sister who both lived in New York, and he did not want to disgrace them. Unsure of what to do, prison staff released his body to Theodore Auman’s Funeral Home. Auman injected Penn with an experimental embalming fluid in an attempt to preserve his body until his identity could be found, or his remains were claimed. His description at time of death was given as having a light mustache and brown hair, weighing 159 lbs and a height of 5’11”.

With Penn’s last breath came the beginnings of a story that could only play out in the age in which it occurred. The prosperity that mass industrialization brought to the Victorian Era was revolutionizing the way society lived. However, death was still in the forefront of everyday life. Mothers frequently died in childbirth, hangings still occurred in public squares and diseases ravaged entire families. While Auman using an unidentified man for his experimental embalming practices could be regarded as barbaric by today’s standards, it is important to understand the context of that time period. People have not stopped dying, but great strides have been made in medicine and disease control. Being shocked by the prospect of Stone Willie’s existence underlines the progress that he was an essential part of.

On November 22nd the Reading Eagle published an article titled, “A Slight Clue” which revealed that Penn’s cellmate named James Clark had a few pieces of identifying information he claimed Penn confided to him. Clark was arrested the same week as Penn for pickpocketing during the fireman’s convention parade. Clark claimed Penn had told him that he was 41 years of age, and that he was from Waterford, Ireland. He also revealed that his father was a popular hotel-keeper and ran a public house on the market square there for three decades. He also claimed he was a saddler, and said he traveled extensively around the country. Most specifically, Penn said he came to America at the age of 10 from Waterford. If this information Clark relayed is true, that makes Penn born in 1854 and his immigration to America occurring roughly in 1864.

No one came to claim Penn’s body. Over a week after his death, a clipping in the November 20th, 1895 Reading Times stated that his body would be sent to a Philadelphia Medical college, “as the law in such cases directs”.

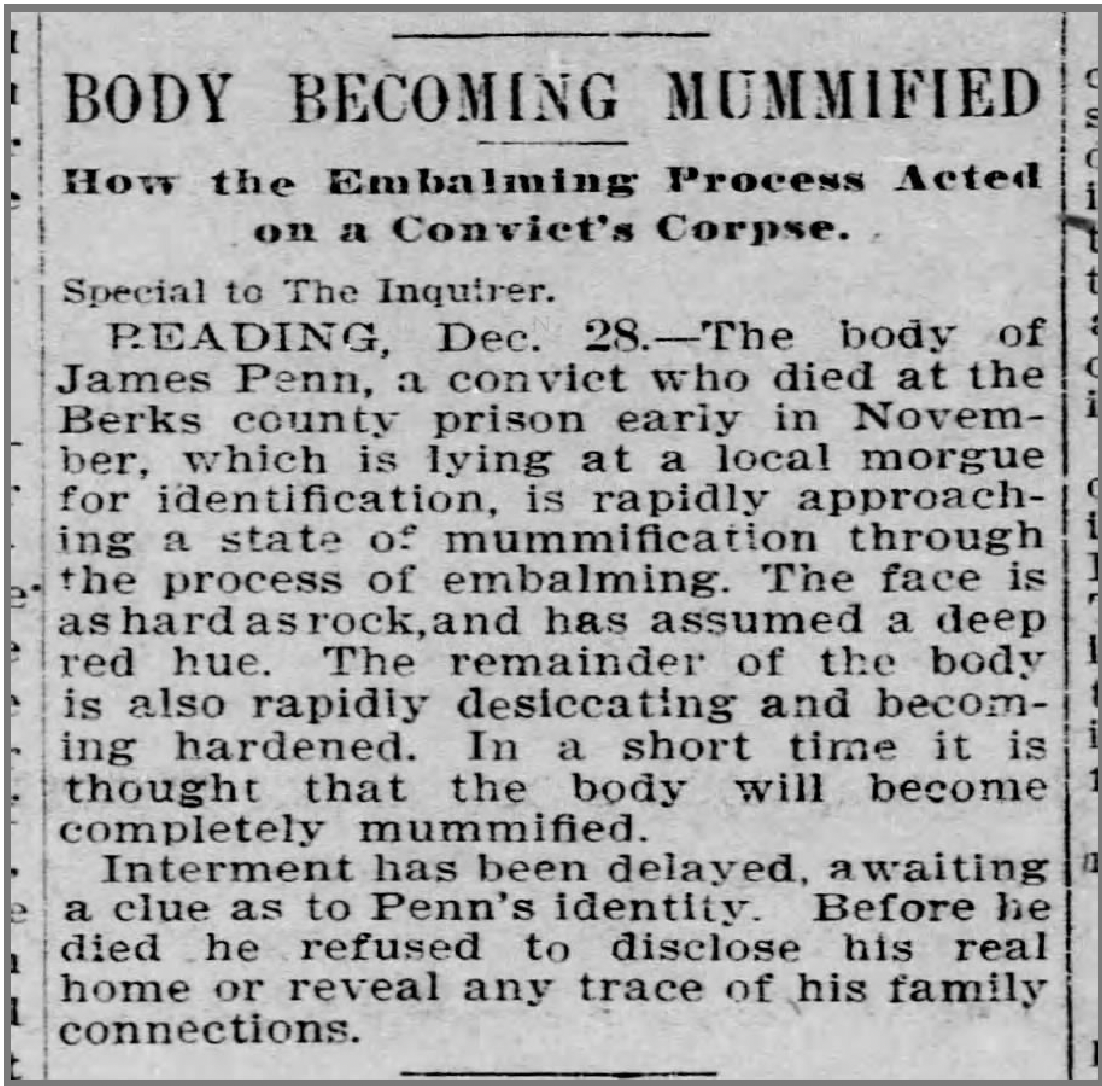

Over a month later on Sunday December 29th, a Philadelphia Inquirer article titled, “Body becoming Mummified” explained that Penn’s body was rapidly approaching a state of mummification through the process of embalming. The article states that “the face is as hard as a rock and has assumed a deep red hue”. Interment was awaiting any more clues on Penn’s true identity. None would surface and a wild goose chase had begun.

Berks County Prison’s Warden Kintzer wrote to the Mayor of Waterford, who disclosed there was a man by that name who kept a hotel but had recently died. The Mayor also disclosed that a daughter of that man ran a hotel in Dublin. When the Warden wrote to her, she claimed her brothers were dead.

A February 6th, 1896 Times clipping indicated that the board of Berks County Prison directed Auman to dispose of the body of James Penn, effectively ending their involvement with the corpse.

When the investigation by the prison warden dropped off, Auman himself picked up the trail. The Wilkes-Barre Times reported on March 7th, 1896 that Undertaker Auman had corresponded with officials in Wilkes-Barre in reference to the identity of James Penn. It states Auman was sure the man’s real name was James Murphy of Wilkes-Barre. This lead didn’t seem to pan out either.

That was the very last public mention in regards to identifying his corpse at Auman’s. Or was it?

An article published in the Reading Times on March 23rd, 1898 added a new dimension to this story. It was titled, “Body 13 months in Morgue: the embalmed remains of Michael Poronski who committed suicide in 1897”. The article reported that this corpse was also at Auman’s in a petrified state. Poronski (also spelled Posonski, Porouski, and Pohouski in various other articles) was arrested on January 12th, 1896 – less than two months after James Penn’s death. He was charged with stabbing another man outside a Polish bar near the corner of seventh and south streets. Goaded by cellmates, Porouski did kill himself in his prison cell on February 17th, 1897. This was perhaps the origin of the falsehood that Stone Willie died by suicide.

According to a story in the June 14th, 1901 Reading Times, a Polish man believed that the Pohouski mummy may be the body of his late brother. He visited Auman’s but couldn’t for sure identify the body and said he would be back.

Just a week later on June 20th, 1901 the Reading Times reported that the Pohouski mummy was positively identified by two completely different men, Philadelphian Paul Molson and F.J. Sebest, saloonkeeper at 623 Willow Street in Reading. Sebest was quoted in that article “I thought his body had been buried. He sometimes came to my saloon. I never read such a body being at Auman’s. No, I will not give his right name, He was known as Michael Pohouski. Let it go at that.”

Pohouski was buried in Aulenbach’s Cemetery shortly after. He is definitely not the Stoneman Willie that anyone reading this may have visited; though this begs the question – exactly how many mummies did Auman create? Who was Theodore C. Auman, anyway?

Theodore C. Auman

Auman began his mortician career at the age of 20 in 1889 in a small building at North 3rd Street. He moved to the current 247 Penn Street site in 1902; which means Stone Willie’s body made that move also. It also means that the small building on North 3rd street was home to at least two mummies for a four year period between 1897-1901.

Auman’s obituary mentioned his generous philanthropic efforts; though always quietly, never wanting to be named. Mortuary business was only a part of his dynamic portfolio, which also included owning various theaters along Penn Street. He was responsible for opening Reading’s very first nickelodeon, the “Mecca Theatre”, at 7th and Penn.

Auman was considered a pioneer of modern methods in the conduction of funerals and was one of the first to establish a funeral parlor. Previous to this, funerals generally occurred in the residence of the deceased.

In 1927, Auman hired renown Philadelphia architects Rabenold & Seyburger to construct the stone mansion that sits on the circle of Reading and Wyomissing Boulevards. He enjoyed over five years in this stunning architectural display of wealth until he died peacefully in his sleep on January 6th, 1933. His body was found in bed by his butler. The stone mansion now addressed 1198 Reading Boulevard is currently for sale, and for only $1.6 million you can wake up in the bedroom that Theodore C. Auman didn’t.

The Auman mortuary business continued under son Theodore C. Auman Jr and Son-in-law Earl Angstadt until 1975; when Theodore C. Auman III became the third generation to continue his grandfather’s legacy. Theodore C. Auman III died in 2008 and the company was eventually bought out by Dignity Memorial, a regional chain of funeral homes.

A Visit to Stoneman Willie and Surprise Scientific Revelations

On Friday, May 12th, 2023 I went into Auman’s Funeral Home to live the Stoneman Willie experience. Willie was laid out in his blue pajamas in a coffin in a large room on the second floor. His reddish-brown hair was completely intact and his mouth was slightly open revealing jagged teeth. A brownish-red hue best describes the color of his leathery skin. Contrary to popular belief, his fingernails did not continue to grow post-mortem. This phenomena is caused by the embalming agent which makes the skin shrink, revealing more nail.

After this visit I headed to Berks History Center’s library to see if there was anything there that could be added to this story. I did not expect to find anything that I had not already seen in the Eagle and Times newspapers archives. I was very wrong.

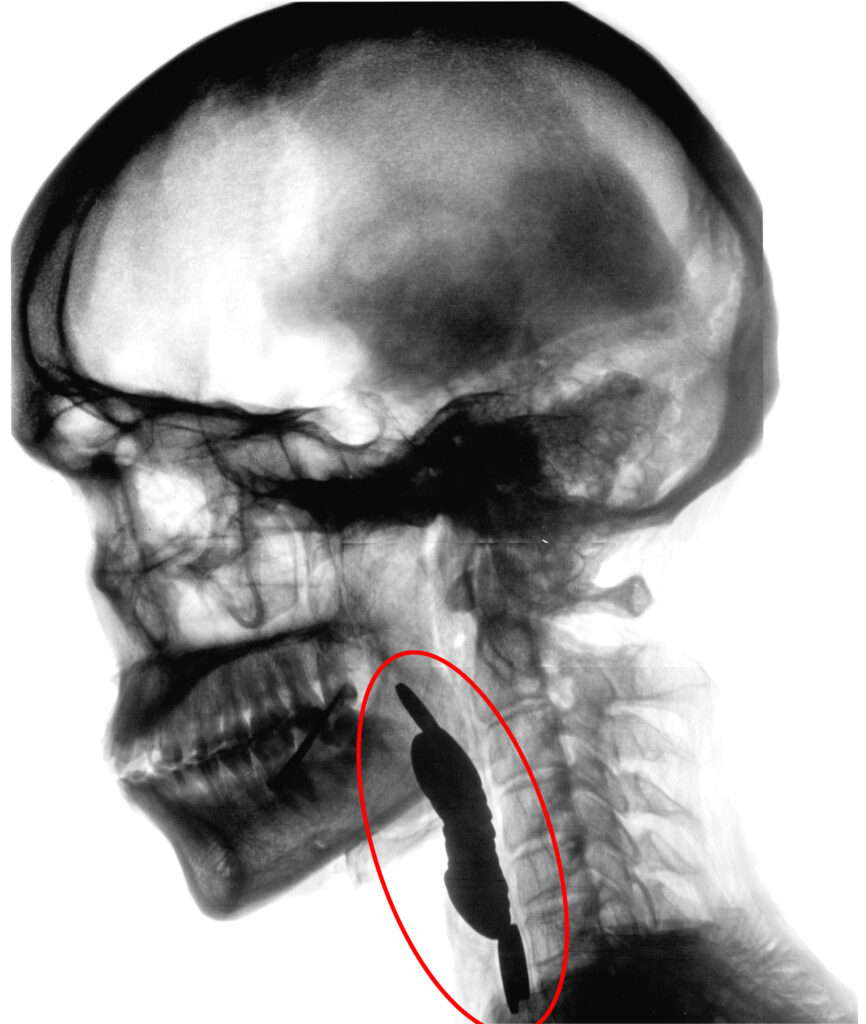

There was a file waiting for me full of x-ray images taken in 2004 that were a part of a scientific study on Stoneman Willie. Most fascinatingly, these x-rays revealed that coins were present in Stoneman Willie’s esophagus.

Perplexed by the fact that this scientific research had gone unnoticed by our local community, in addition to wanting an explanation about the coins; I contacted Gerald Conlogue, the Mummy expert and researcher responsible for that 2004 study. Conlogue is now a retired professor emeritus from Quinnipiac University. His involvement with Stoneman Willie stemmed from connections made while working as host of National Geographic’s television production titled The Mummy Road Show, which aired 39 episodes over three seasons between 2001-2003. While the knowledge of Stoneman Willie’s existence reached Conlogue too late to be a part of The Mummy Road Show, Auman’s allowed him to conduct research privately. The results of that research are compiled in a chapter dedicated to Stoneman Willie in a book Conlogue and his colleague Ron Beckett are writing.

A total of 21 coins were retrieved from Willie’s throat during this study which revealed them to be pennies dated between 1896 and 1961. This means that visitors of Willie’s were intentionally and perhaps secretly putting the coins into his mouth over the course of nearly 70 years. It was surmised by colleagues of Conlogue’s that this was done as a part of a European ritual which dates back to the Greeks and Romans; where coins were placed in the mouth of the deceased to pay their way across the River Styx.

The researchers also took images of his internal organs, and while they had shrunken considerably due to the embalming process, some speculations were able to be drawn about his manner of death.

Imaging of the kidneys, liver, pancreas, spleen and lungs were conducted to see if the damage from alcoholism, his stated ailment, could be proved present. Despite the 1895 diagnoses of acute uremia, nothing conclusively abnormal was present on the kidneys or liver. However, several areas of the lungs had what the radiologist felt may have been a collection of material. Those findings suggest that an existing pulmonary infection was present at the time Stoneman Willie died. So it can be loosely concluded that the infection which poisoned his blood and led to organ failure did not originate in the kidneys but the lungs.

A sample of tissue was taken from Stoneman Willie to determine the contents of the experimental embalming fluid Auman used. An examination by David Henderson Ph.D, chemistry professor from Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut revealed that the preservative Auman used was formalin. According to Conlogue’s report, “formalin is the common chemical name for a 35-40% solution of formaldehyde in water“. Lending truth to the legend that Auman found his embalming concoction in an old German meat preservation book; prior to 1897 formaldehyde was primarily produced in Germany. It wasn’t until after 1900 that it became commercially available in the United States. Conlogue concluded that Auman could have been one of the very first embalmers in the country to use this chemical as a human preservative.

Impending Burial

On April 26th, 2023 WFMZ broke the story that Willie’s caretakers at Auman’s were in the very initial stages of planning a burial. During a press conference on June 1st the funeral home revealed that Willie will be a part of Reading’s 275th anniversary parade on Oct 1st, a public viewing will be held between Oct 2-6 and his burial will occur on Oct 7th. Poetically, that week is also the 128th anniversary of the firemen’s convention week and his initial arrests.

With under 6 months until Stoneman Willie’s interment, the window of opportunity into investigating his true identity is closing. The truth that has eluded us for generations is out there. A quick search on Ancestry.com reveals via New York arriving passenger ship records that 2,101 ten year old Irish boys made the voyage to America in 1864.

This leaves many wondering if it is possible for us in 2023 to close the chapter on Stoneman Willie that our ancestors could not. After all, it was Auman’s original intention to preserve Penn’s remains until he could be identified. It has been nearly 20 years since the first study and Gerald Conlogue says he is willing and eager to put a team together to perform some final tests on Stoneman Willie before he is lost forever.

What say the locals? I posed the question in poll form to a select group of my Facebook and Instagram followers, “With DNA testing advancements and the availability of global historical records; Should an attempt be made into finding Stoneman Willie’s real identity before his impending burial?“.

The vast majority (80%) answered yes.

If the account Clark gave about Penn’s origins were true, perhaps the truth lies in the 1849-1890 Waterford News archives, readily available on Newspapers.com. Or maybe insight into his father’s hotel is in the 1894 publication titled, “History Guide and Directory of County and City Waterford” viewable on Ancestry.com. If Conlogue would be allowed to retrieve samples, DNA testing could confirm his Irish heritage, even pinpoint a region.

A true testament to 128 years of progress in scientific and historical research; perhaps with cooperation from Willie’s caretakers we could crack this mystery wide open and bury him under a stone bearing his true name.

This article was made possible thanks to archivist Bradley Smith from Berks History Center’s Janssen Library and also Gerald Conlogue, Professor Emeritus at Quinnipiac University.

Fascinating details. Hadn’t thought about this in ages. Thanks for posting these articles about the old home town.

Excellent investigation and reporting. Well done.

Fantastic report

Thank you for all of your efforts

I would love to see his true identity

A really well researched article! Better than the others news outlets are putting out right now in light of his burial.

Thank you, for the kind words and for googling! I posted this back in May, seems like everyone else is just catching up ☺️

Great article!

Excellent article – Berks is lucky to have talent like yours! Landed here from a CNN video report of Oct 4th, 2023, “Man who was accidentally mummified 128 years ago is getting a funeral this weekend.” Seems his identity will be revealed at the funeral, so the quest has paid off.

Thank you very much Chris! I like to think I played a small part in the push to identify him. I will be there on Saturday to find out. Thanks for digging deeper and finding my article!

I grew up in Reading but never had heard of Willie until I saw the recent news coverage. I happened to be in town yesterday on family business and stopped by Auman to catch a glimpse of his body before he’s interred on Saturday. He’s been dressed in period-appropriate attire and is in one of the viewing rooms of the home so the public can see him before he’s sent off. Here’s a link to some pics I took while there:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/bgohacki/albums/72177720311721858

Thanks for sharing your photos!

This post is a prime example of your expertise and ability to engage readers. Excellent work!

Great information shared.. really enjoyed reading this post thank you author for sharing this post .. appreciated

Brilliant work on this article! You’ve covered the topic comprehensively and yet made it extremely relatable.

Your article was not only informative but also very well-written. You have a talent for communication.

Awesome article! The bit about the “Formaldehyde for preserving meat, described in a German chemistry book” is very interesting to me. In this era, almost all chemical literature was written only in German, so it makes sense that this story would occur in an area like ours that had such a large German-speaking population.